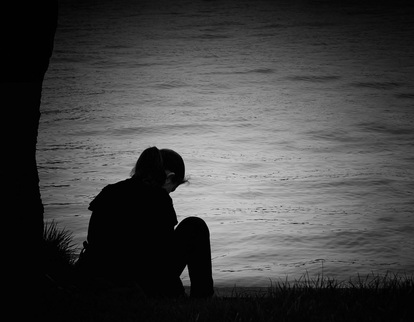

She spoke slowly and with obvious caution. Talking about religion or spirituality did not come easily. She was not certain why she was intrigued. It was new and uncomfortable, but something powerful pushed her to continue.

Once, life seemed intact. There was a town and a church, family, school and friends. Now that seemed far away. She grew and moved. Education opened a life of possibility. There were new friends and a new town, and it all appeared to fit. Now she realized that it didn’t. Something was missing.

It wasn’t religion. She left that behind in childhood. No one could believe that stuff—she said “stuff” with angry emphasis. But the friend who was listening did not seem bothered.

She was “spiritual,” but she was unsure what that meant. And there was another problem. Many people say they’re spiritual, but none of them seemed like her. She needed a group, a place where people understood. She was trying to live several lives at once, but she couldn’t hold it together.

There is sad irony in her rejection of religion. The word “religion” refers to being bound, tied together. It is akin to the word “ligament,” where there is a taut connection. The image is instructive. In theory, religion should bind broadly. In practice, narrow, like-minded groups often result. How can religion bind people beyond our differences?

“What if your church had speakers from different religions,” she challenged. “What if you had groups where people like me could sort it out? That might be a start. What do your people know about Islam? Judaism? How do you talk to atheists?”

Her questions are haunting. It is today’s challenge. Congregational preoccupations must be balanced by doors open wide. She is not alone. Accepting her challenge may be the only viable future for “religion.”

William L. Sachs

Once, life seemed intact. There was a town and a church, family, school and friends. Now that seemed far away. She grew and moved. Education opened a life of possibility. There were new friends and a new town, and it all appeared to fit. Now she realized that it didn’t. Something was missing.

It wasn’t religion. She left that behind in childhood. No one could believe that stuff—she said “stuff” with angry emphasis. But the friend who was listening did not seem bothered.

She was “spiritual,” but she was unsure what that meant. And there was another problem. Many people say they’re spiritual, but none of them seemed like her. She needed a group, a place where people understood. She was trying to live several lives at once, but she couldn’t hold it together.

There is sad irony in her rejection of religion. The word “religion” refers to being bound, tied together. It is akin to the word “ligament,” where there is a taut connection. The image is instructive. In theory, religion should bind broadly. In practice, narrow, like-minded groups often result. How can religion bind people beyond our differences?

“What if your church had speakers from different religions,” she challenged. “What if you had groups where people like me could sort it out? That might be a start. What do your people know about Islam? Judaism? How do you talk to atheists?”

Her questions are haunting. It is today’s challenge. Congregational preoccupations must be balanced by doors open wide. She is not alone. Accepting her challenge may be the only viable future for “religion.”

William L. Sachs

RSS Feed

RSS Feed